You can be great at memorising facts and still lose an argument in seconds. Often, the problem is not what you know, but how you think. That is where logical fallacies for students come in.

Logical fallacies are sneaky errors in reasoning that make arguments look stronger than they really are. Teachers, classmates, social media posts, even news headlines can all contain these hidden traps. If you cannot spot them, you can be persuaded by weak or unfair points without realising.

This guide walks through what logical fallacies are, common examples you will see in lessons and debates, and simple ways to call them out without turning every discussion into a row.

Key Takeaways

- Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning that make arguments misleading or weak.

- Learning to spot fallacies improves essays, debate performance, and exam answers.

- Many fallacies follow repeatable patterns, so once you know them, they are easier to catch.

- You can challenge fallacies politely by asking for evidence or clearer definitions.

- Practising with friends, essays, and everyday media sharpens your critical thinking.

Table of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- What Are Logical Fallacies?

- Why Logical Fallacies Matter For Students

- Common Logical Fallacies Students Meet

- How To Call Out Logical Fallacies Without Starting A Fight

- Practice Spotting Fallacies In Everyday Study Life

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions About Logical Fallacies For Students

What Are Logical Fallacies?

A logical fallacy is a flaw in the structure of an argument. The conclusion might still be true, but the reason given for it does not actually support it.

For example, saying,

“My friend got an A without revising, so revision is pointless”

is not a good argument. One friend is not enough evidence to support a general claim. That is a type of fallacy.

For more formal definitions and lists, it can help to check a clear guide such as Logical Fallacies | Definition, Types, List & Examples.

Once you know the patterns, you start to see them everywhere: in essays, politics, adverts, TikTok rants, even group chats.

Why Logical Fallacies Matter For Students

Learning logical fallacies is not only for philosophy students. Spotting them helps you:

- Write stronger essays, with cleaner reasoning and fewer weak claims.

- Take part in debates without relying on cheap shots or personal attacks.

- Analyse sources in subjects like history, science, and politics.

- Protect yourself from dodgy arguments online and in the news.

Good arguments are also about fairness. Understanding fallacies trains you to argue against the idea, not the person. For better quality debate, you might find it helpful to read about Steelmanning your opponent’s arguments, which is almost the opposite of using fallacies.

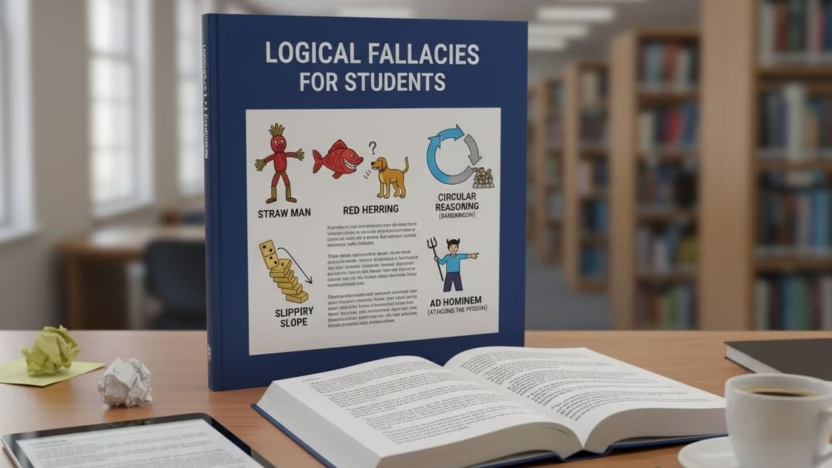

Common Logical Fallacies Students Meet

There are many fallacies, and different sources group them in different ways. A handy overview is the list in 15 Logical Fallacies to Know, With Definitions and Examples.

Here are some of the most common types you are likely to see in class work, essays, and student debates.

1. Ad Hominem (Attacking the Person)

Pattern:

Instead of attacking the argument, someone attacks the person making it.

Example:

“Do not listen to her point about climate policy, she skipped science last week.”

Skipping class does not prove her argument wrong. It only attacks her character.

How to call it out:

- “That comment is about the person, not the actual argument.”

- “Can we focus on the reasons, not who is giving them?”

2. Straw Man (Misrepresenting the Argument)

Pattern:

Someone changes your argument into a weaker version, then attacks that weaker version.

Example:

Alex: “I think we should limit phone use in lessons.”

Sam: “So you want to ban phones completely and go back to the 19th century?”

Alex never said that. Sam created a straw version of the view, then attacked it.

How to call it out:

- “That is not what I said. My actual point was…”

- “Can you restate my view in your own words so we are sure you have it right?”

This links well with the habit of steelmanning, which is explained in the article on How to steelman opposing views effectively.

3. Slippery Slope (One Step Will Lead To Disaster)

Pattern:

Claiming that a small first step will automatically lead to a chain of bad events, without showing why.

Example:

“If we let students sit at the back, next they will refuse to listen, then no one will pass exams.”

Could it happen? Maybe, but it is not guaranteed. The argument ignores other factors and jumps to the worst outcome.

How to call it out:

- “You have moved from one small change to a huge result. What links those steps?”

- “Can you show evidence that this first step usually leads to that final outcome?”

4. Hasty Generalisation (Too Little Evidence)

Pattern:

Making a general rule from too few examples.

Example:

“I met two rude people from that school, so everyone there is rude.”

Two people are not enough to judge a whole school.

How to call it out:

- “Your sample is very small. Do you have broader data?”

- “Those examples might be true, but they are not enough to prove the general claim.”

5. False Dilemma (Only Two Options)

Pattern:

Presenting a situation as if there are only two choices, when in fact there are more.

Example:

“Either you support this new homework rule, or you do not care about your grades.”

There are many possible views in between. You might care about grades and still think the rule is bad. The Common Logical Fallacies classroom activity uses false dilemma examples that often appear in school settings.

How to call it out:

- “There might be more than two options here.”

- “Can you explain why you think these are the only choices?”

6. Appeal To Authority (Trust Them Because They Are Important)

Pattern:

Saying something must be true only because an authority figure believes it.

Example:

“This revision method works because a famous YouTuber said so.”

Experts and creators can be helpful, but their status does not replace evidence.

How to call it out:

- “What evidence did they give? Can we check it?”

- “Their view is interesting, but can we look at some actual data or studies?”

For a more detailed breakdown of different fallacy types and how they fit into categories, you can read How to Argue Against Common Fallacies.

How To Call Out Logical Fallacies Without Starting A Fight

It is easy to sound rude if you shout “fallacy!” every five minutes. Instead, use calm questions that keep the focus on the idea, not the person.

Helpful phrases include:

- “Can you explain how that example proves your main point?”

- “Could there be more than two options here?”

- “Is that about the person, or about the argument?”

- “Do we have enough evidence to say that about everyone?”

You can also share what you are doing:

“I am trying to check for logical fallacies so my own thinking gets better. Can I ask a few questions about the argument?”

This makes it feel like a shared project to improve reasoning, not a personal attack.

Practice Spotting Fallacies In Everyday Study Life

You remember fallacies better when you apply them in real situations rather than only in theory. Here are some quick ways to build the habit.

In Group Study And Debates

When you work in groups, you will hear lots of claims about what will or will not help with exams. Use these as practice material.

During your next group session, ask the group to pay attention to the structure of arguments, not only the answers. The article on Group study tricks for teamwork has ideas for debates and teach-backs that fit well with fallacy spotting.

You might:

- Pause when you hear a bold claim and ask for the reasoning.

- Collect examples of different fallacies on a shared document.

- Try to fix weak arguments together so they become stronger and fairer.

In Essays And Exam Practice

When you write essays, check your own paragraphs for fallacies. Ask yourself:

- “Have I jumped from one example to a big claim?”

- “Did I attack a writer instead of their evidence?”

- “Am I acting as if there are only two possible views?”

Over time, you will cut out weak links before your teacher ever sees them.

In Media, Social Posts, And Everyday Talk

Fallacies are everywhere: in adverts, political speeches, and comment sections. Pick one fallacy per week, look out for it, then note down any examples you see.

If you enjoy tech and new learning tools, you might like reading about AI and VR enhancing critical thinking. These tools often raise bold claims about learning, which are perfect for testing your fallacy radar.

Conclusion

Logical fallacies are not just a topic for exams. They shape how you judge ideas every day, from classroom debates to social media arguments. If you can spot and question these errors, your thinking becomes clearer and your conversations become fairer. That is the real power of critical thinking.

Next time you hear a bold claim, pause for a second. Ask what kind of reasoning is behind it, and whether any of the fallacies in this guide are hiding in the background. With practice, you will not only win more arguments, you will also understand people and ideas on a deeper level.

Frequently Asked Questions About Logical Fallacies For Students

Are logical fallacies always used on purpose?

No. Many people use fallacies without realising. We are all biased by habits, emotions, and quick thinking. Learning about fallacies helps you spot them in your own arguments as well as other people’s.

How many logical fallacies should students learn?

You do not need to memorise every single type. Start with common ones like ad hominem, straw man, slippery slope, hasty generalisation, false dilemma, and appeal to authority. Once you are comfortable with those, you can explore longer lists such as the Master List of Logical Fallacies.

How can I revise logical fallacies for exams?

Make flashcards with the fallacy name on one side and a simple definition plus your own example on the other. Test yourself by spotting fallacies in past papers, sample essays, and articles online. You can also use resources like Logical Fallacies | Definition, Types, List & Examples for extra examples.

Do teachers ever use logical fallacies?

Yes, teachers are human too. They might use a weak example or rushed reasoning, especially when speaking off the cuff. The goal is not to “catch” them out, but to train your brain to separate strong and weak reasoning, whoever is speaking.

Is pointing out fallacies rude?

It does not have to be. The key is your tone and wording. Ask questions instead of making accusations, and keep your focus on the argument, not the person. If you are polite, many people will appreciate that you care about clear thinking.